A new lawsuit sheds light on New York’s licensing of 10 medical cannabis operators in 2015 and 2016, raising questions about how regulators scored the applications and whether other unsuccessful applicants could raise their own legal objections.

Fresh lawsuits could slow the process of handing out additional MMJ licenses – at a time when state lawmakers and the governor are debating legislation to approve a new adult-use program.

In its lawsuit filed Feb. 5 in Albany County Supreme Court, New York-based Hudson Health Extracts (HHE) claims that its MMJ application in 2015 merited a top-five ranking if it weren’t for the state Department of Health’s “arbitrary, capricious, and irrational decisions.”

Such litigation isn’t unusual in marijuana licensing, nor is the language of the allegations.

But what makes HHE’s case so striking is that the company appears to have had the credentials that would make for a successful applicant:

- $18.6 million of capital.

- Experience producing medical cannabis in the highly regulated states of Connecticut and Minnesota.

- A research partnership agreement with Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx.

- $1 million spent to secure real estate, including a contract for a manufacturing site and dispensary leases.

Yet HHE ranked 13th among 43 applicants with a financial standing score of “average.”

If the company had received an “excellent” financial score, it would have won a license.

HHE was founded by Mitch Baruchowitz, managing partner of Merida Capital Holdings, a New York-based private equity firm.

Among the marijuana firms he co-founded were LeafLine Labs, which won an MMJ license in Minnesota, and Theraplant, which won a medical cannabis permit in Connecticut.

It took years for HHE’s administrative appeal to the state of New York to be heard and decided.

Finally, in July 2019, Administrative Law Judge William Lynch ruled the health department’s decision not to grant HHE a license was correct, a position the state adopted in January 2020.

MMJ program strife

Since launching in 2016, New York’s medical marijuana program has experienced turnover involving half of its 10 vertical licenses. That in part is because of financial difficulties afflicting the original license holders.

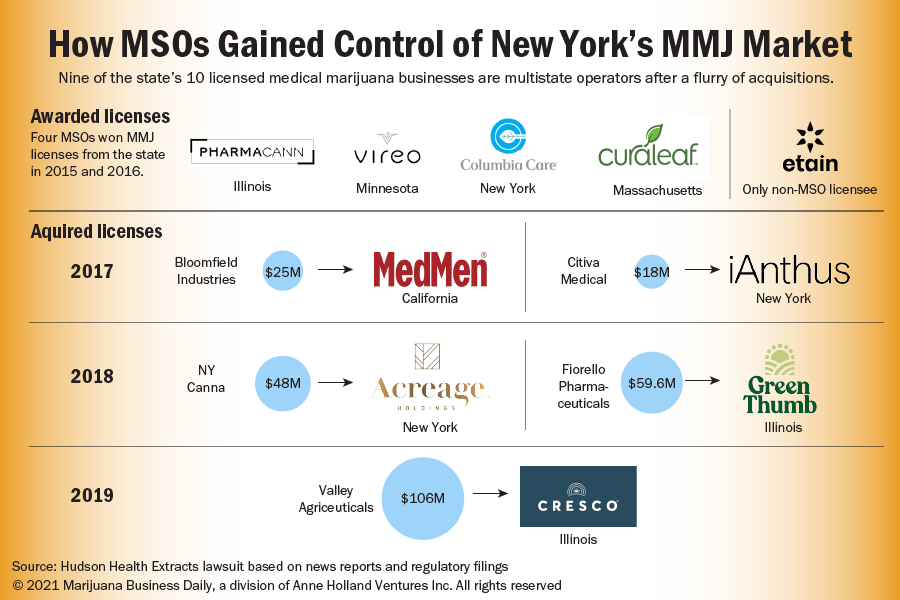

Nine of the 10 current licensees are multistate operators (see chart above), with five having secured their licenses after purchasing them from a local company.

Some of the MSOs are struggling financially, most notably Los Angeles-based MedMen Enterprises and New York-headquartered iAnthus. The latter went through a financial restructuring in a Canadian court.

Hudson Health Extracts argues in its lawsuit that “much of the dysfunction that currently bedevils New York’s medical marihuana (marijuana) program, in fact, stems from the Department’s award of registrations to companies … that lacked the operational competence and the financial resources necessary to build a capital-intensive cultivation facility, run a processing plant, and sustain four retail locations spread across the state, rather than to companies like HHE, which boasted both operational competence and prolific financing.”

HHE attorneys declined to comment beyond the lawsuit.

Jill Montag, public information officer for the New York health department, wrote in an email to Marijuana Business Daily that the agency “does not comment on pending litigation.”

Some claims stick out

Cannabis attorney Rob DiPisa of Cole Schotz in New Jersey said the suit is persuasive.

But he added it’s worth noting the application process was six years ago and New York’s first go at marijuana licensing.

Observers must be a “little empathetic,” he noted, because regulators were “tasking unsophisticated government officials with the responsibility to review very technical aspects in the applications.”

Still, DiPisa said three things struck him about HHE’s claims:

- The lawsuit cites a correlation between the amount of money companies spent on lobbying local and state officials and those who received licenses.

- Assessing financial numbers doesn’t require sophistication; it’s pretty black and white.

- State regulators changed the way they weighted certain factors, according to the suit.

The lawsuit cites an investigation by the Lower Hudson Journal News in 2017 that found the six companies that spent the most on marijuana lobbying in New York all won MMJ licenses.

In the Journal News’ report, a state health department spokesperson disputed the suggestion that money influenced the licensing decisions.

More lawsuits?

If HHE is given a license as a result of this challenge, DiPisa said, “others may view this as an alternative avenue to obtain a license, and then you may see more lawsuits and that could lead to the potential slowdown” of additional licensing such as what’s happened in New Jersey.

Avis Bulbulyan, CEO of Los Angeles-based cannabis consulting firm Siva Enterprises, is watching the suit closely because of his work in preparing the unsuccessful license application in New York for the minority- and physician-led Alternative Medicine Associates (AMA).

If Hudson Health Extracts’ lawsuit is successful, Bulbulyan said, he wants to know how the state will adjust for the fact that AMA ranked even higher than HHE in the application scoring.

Bulbulyan said AMA, which has reserved its legal rights, had the second-highest raw score, but the weighted average “brought us to 12th.”

He said “no other application process was as heavily detailed and involved and cumbersome” as New York’s. He emailed photographs of AMA submitting 10 banker’s boxes of application materials.

HHE’s lawsuit said that most applications were more than 1,000 pages and that the winning applications averaged 2,000 pages.

“Whenever you get that detail, the scoring always becomes pretty arbitrary,” Bulbulyan said.

‘Average’ financial standing

New York’s medical marijuana law, the Compassionate Care Act, was enacted in July 2014.

Five vertical licenses were awarded in July 2015, and five more were issued roughly a year later from the original pool of 43 applicants.

New York hasn’t granted any new MMJ licenses since.

The state has 140,000 registered MMJ patients and 38 dispensaries that will reach sales of about $250 million-$350 million this year, according to Marijuana Business Factbook.

By comparison, Florida, which didn’t open up its market to full-strength MMJ until 2017, has 491,370 patients, 315 dispensaries and is projected to reach $1 billion-$1.225 billion in sales this year.

HHE was one of at least 15 unsuccessful applicants to request an administrative hearing.

Administrative hearings didn’t begin until January 2018 – 2 ½ years after initial permits were granted.

A consolidated hearing with seven petitioners, including Hudson Health Extracts, ran through June 2018, then the cases were separated and it was another year until the decision was made on HHE’s case.

Judge Lynch concluded that three health department employees “credibly testified” that measures were taken to foster consistency in the scoring process.

HHE argues in its suit that the state handpicked the three who testified, at least 11 reviewers didn’t testify in the case and the company was barred from calling rebuttal witnesses.

Despite its war chest of $18.6 million, HHE was one of 38 applicants that received the same “average” score for its financial standing, according to the lawsuit.

“In other words, the Department concluded (inexplicably) that HHE’s $18 million was equivalent to the zero dollars or negative balance sheets submitted by other applicants,” the lawsuit notes.

Had Judge Lynch simply corrected this “single, glaring mistake” and awarded HHE one point extra for having “excellent” financial standing, the company would have won an MMJ license.

HHE’s lawsuit noted the state’s decision to grant a license to Bloomfield Industries, which lacked capital, was headed by a 26-year-old with no previous experience and reportedly soon ran into financial difficulties.

Bloomfield was sold early in the program – in 2017 to MedMen.

One of the state’s application evaluators acknowledged in the HHE case that the reviewers didn’t have time to thoroughly examine all the applications because they were under pressure to complete the process within eight weeks.

“It was really just grabbing and scoring because we were under a tight timeline for doing this . . . we didn’t have the luxury of, you know, perusing these (applications) in a slow fashion,” the state health department’s senior witness, Dr. Anne Walsh, testified.

Jeff Smith can be reached at [email protected].

Medical Disclaimer:

The information provided in these blog posts is intended for general informational and educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. The use of any information provided in these blog posts is solely at your own risk. The authors and the website do not recommend or endorse any specific products, treatments, or procedures mentioned. Reliance on any information in these blog posts is solely at your own discretion.